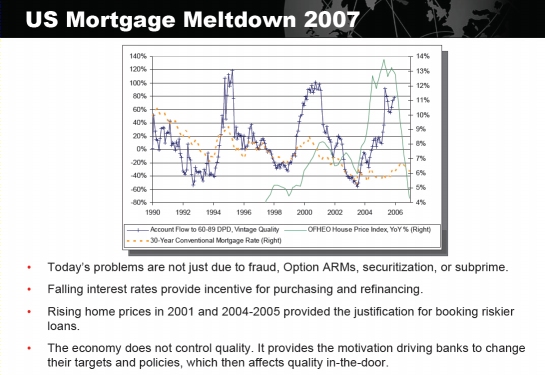

During a panel at Fair Isaac’s Interact conference last week, a banker from Abbey National in the UK suggested that part of the credit crunch was due to the use of the FICO score. Unlike other panelists, who were former Fair Isaac employees, this gentleman was formerly of Experian! So there was perhaps some friendly rivalry, but his point was a good one. He cited an earlier presentation by the founder of Strategic Analytics that touched on the divergence between FICO scores and the probability of default. The panelist’s key point was that some part of the mortgage crisis could be blamed on credit scores, a point that was first raised in the media last fall.

During a panel at Fair Isaac’s Interact conference last week, a banker from Abbey National in the UK suggested that part of the credit crunch was due to the use of the FICO score. Unlike other panelists, who were former Fair Isaac employees, this gentleman was formerly of Experian! So there was perhaps some friendly rivalry, but his point was a good one. He cited an earlier presentation by the founder of Strategic Analytics that touched on the divergence between FICO scores and the probability of default. The panelist’s key point was that some part of the mortgage crisis could be blamed on credit scores, a point that was first raised in the media last fall.

The FICO score is not a probability.

Fair Isaac people describe the FICO score as a ranking of creditworthiness. And banks rely on the FICO score for pricing and qualification for mortgages. The ratio of the loan to value is also critical, but for any two applicants seeking a loan with the same LTV, the one with the better FICO score is more likely to qualify and receive the better price.

Ideally, a bank’s pricing and qualification criteria would accurately reflect the likelihood of default. The mortgage crisis demonstrates that their assessment, expressed with the FICO score, was wrong. Their probabilities were off.

- Was the FICO score a useful metric of creditworthiness before the crisis but not during?

- Is the FICO score a reliable metric going forward?

In these mid-crunch days, Fair Isaac is reminding its customers that the FICO score is a ranking not a probability. The underlying point they seek to make is that the relationship between the FICO score and the probability of default is more complex and dynamic than their banking customers understood last year. (Another post on predictive analytics also discussed stationarity.)

It’s the probability that matters, not the score!

In his keynote, Ian Ayres also focused on the inadequacy of scores.

He was explicit that bankers need the probability of default and, further, that they need to know how reliable such probabilities are. As an example, he cited polls where one candidate is leading by 6 points within a margin of error of 3 points as almost meaningless. More meaningful would be the probability that the leading candidate will win. Even better would be an estimate of the probability of default along with an assessment of the reliability or accuracy of that probability.

Bankers increasingly understand that the FICO score is not the probability of default that they need when originating and underwriting credit. As a result, bankers increasingly understand that there is no adequate external source of the probabilities they need in order to optimize their portfolio performance.

This realization has several ramifications:

- A market opportunity for predictive analytics in credit has opened on Fair Isaac’s turf.

- Scorecards have lost much of their “solutions” luster, becoming just another technique.

But several things also became clear as I talked with numerous practitioners last week. Fair Isaac doesn’t have much competition. In fact, it is shocking how little competition they have in such a large and lucrative market.

What decisioning market?

Although there is a market opportunity for more rigorous decisioning solutions, there is no significant challenger to Fair Isaac. I expected to hear more about the Experian Group, but the only direct competitor identified by more than one person was Austin Logistics. Several people indicated that they were using statistical tools directly, especially SAS, and Fair Isaac itself is placing a great deal of emphasis on its own predictive analytic tools, especially Model Builder.

Note that Vantage Score is really having an impact on Fair Isaac scoring revenues, as reflected in their most recent earnings call transcript. So there is more competition than may seem apparent to the audience that attends Interact.

Another chasm to cross

Generally speaking, this market needs the benefits of broader machine learning techniques, such as statistics, and a more rigorous understanding and emphasis on probabilities. The audience, however, is not technically sophisticated enough to become aggressive adopters, despite recent harsh lessons. In the same panel, every banker in turn solicited risk analysts to join their organizations, headquartered in Asia-Pacific, London, Canada, and on the west coast. They also agreed that it is easier to learn finance than analytics.

The market for analytics is crowded with sophisticated tools and intellectually demanding techniques that are simply too hard for most people to understand and use, let alone to use effectively and reliably. This is precisely the circumstances that decision management was in during the late nineties when business rules technology started going mainstream. In 2000, we crossed that chasm by introducing natural language business rules (see Haley’s Authority). At the same time, Blaze Advisor, now owned by Fair Isaac, was crossing that chasm using a form based approach called “Innovator”.

Similar advances will be forthcoming in analytics. As with business rules, this will not eliminate the need for highly skilled consultants, but their criticality and marginal value will diminish as analytics becomes more effective in the hands of non-experts (and as better solutions develop in key markets, such as in credit, risk, fraud and other criminality or terrorism).

Until it’s easy, use expertise

If you are in this market and could use some help with modeling, analytics, or adaptive decision management, feel free to get in touch. We have some excellent capabilities and partners in these areas. We are happy to help recommend approaches or products, or simply to make referrals. Of course, there are also highly specialized consultancies, such as Strategy Analytics that can give excellent implementation-agnostic advice.

One thing worth noting, but only in passing for now, is Fair Isaac’s acquisition of Dash Optimization. This reflects the increasing trend towards broader and deeper application of technology within credit decisioning. it is also a response to the decline of scoring and the increasing need for decision optimization, which is a broader subject than decision management, with or without predictive analytics and adaptation.

Nonetheless, optimizing portfolios will not optimize profits if the scores used are not reliably correlated with probabilities.

It is also interesting how Ilog and Fair Isaac continue to converge from a technological perspective.

Paul

Normally I find your posts very accurate but today, I fear, I have to take issue:

– The FICO score is not, never was and was never said to me a measure of the likelihood of default on a mortgage. Any lender who took it as such is probably beyond help – they would have taken any other analytic measure and misused it too.

– Scorecards are a technique for PRESENTING an analytic that is defensible with regulators and easy to explain. Scores can be built using any and all analytic techniques and often are. Lots of other techniques, like Neural Nets, can create scores. What they struggle to do is explain them. Scorecards get used because they can be used to explain, not because of any particular predictive power. This has not changed in the current meltdown.

– Vantage is impacting scoring revenues because the bureaus are practically giving it away, necessary to promote adoption, and the lenders can obviously use this to create price pressure on Fair Isaac. I don’t know but I suspect that every Vantage user is also using the FICO score. Competition, yes, but just another version of the same kind of model created to try and capture some of Fair Isaac’s revenue not to create any new kind of score.

I do agree that there is a huge gap in the analytics world figuring out how to bring non-technical (in this case non-statistical) people into the process to enable effective collaboration. The rules community has done a lot here, the process community a little, the analytic community almost nothing. This needs to change.

I actually started the comment simply to point out that ILOG’s recent release of a scorecard modeler (blogged about here) is another sign of convergence but you had made some unusually sloppy statements that I felt needed correction.

I would not disagree with you, James, that the FICO score was not intended as a probability, but practically speaking, that is how it has been used. Dr. Breeden’s presentation specifically addresses how lenders do not account for the variation between FICO scores and probabilities through interest rate and real estate cycles. My thesis here is not that scores are useless but that probabilities are better and more direct.

Yep, Vantage is a nasty, effective move by the credit agencies against Fair Isaac’s prior monopoly. I feel for Fair Isaac on that one. But Dr. Greene, FICO CEO, explicitly acknowledged the continuing negative impact of Vantage on revenues.

So, I think my facts are in order, I’m afraid. But I truly understand how upsetting the recent wounds from sloppy lending practices and unfair competition are to those who have enjoyed working with Fair Isaac.

As for Ilog’s announcement, I was going to blog on that today! I’ll pass now that you’ve covered it.

Respectfully, Paul

I think FICO score still proved as areliable tool in measuring relative probabilities. Another thing, the crisis started in subprime mortgages – by definition the sector with a higher probability of default. IMHO, considering the width of the problem, it is not the model’s fault, it is the much more general systemic fault of knowing the limitations of the model by the people responsible for the decisions. As is the case with Newtonian physics, for example.

The statistical models are vulnerable to the “black swan” events as a very timely Nasim Taleb’s book has pointed out. It is a bit ironic, that the people putting “past performance” clause into all the fine print, could not apply the same principle to the statistical models that always look at the back mirror. It is too much to expect that FICO score, solely based on individual’s credit behaviour, could predict housing market meltdown, that happened a few years after the most of the subjects happily granted and received their motgages, packaged it and sold to investors as the “the bulletproof” instrument. Last year Goldman and otehr were explaining their losses, as caused by 25-sigma event. Anyone with a slightest bit of statistical knowledge can judge this statement, as being either admission of using the low-touch-with-reality model, or even worse, not understanding it.

Hi Paul,

I’m a little late to this conversation, but I would add the following. If, in the best of all possible worlds, a score like FICO was a nearly perfect predictor of the outcome you want to predict, how would a probablistic score be any better? Now I know that’s a big IF, but the point I’m trying to make is that it may not be the nature of the measurement system that matters so much as the model that is used. In my experience, most models are vastly simplified and consider only the most basic criteria. You wouldn’t size an air conditioning unit by only two of the three dimensions of a space. I see no reason why some stochastic process would be necessarily superior to a scorecard like FICO. It all depends on the quality of the underlying model.

For example, a FICO score gives an indication of credit worthiness at a point in time based on historical information, but it doesn’t explicitly predict whether or not I will default. If my score is 700 today, it will probably be 700 a week from now, even if Lehman Bros. just collapsed and AIG had to be bailed out. It doesn’t take into account those kinds of externalities. And they aren’t all black swans. A model is only as useful as it can predict, and unless it’s robust enough for that, instead of wet finger in the wind, it’s going to fail. As an old statistician myself, I understand the lure of probablistic measures, but down at the bottom of things, it’s the model that counts, and without better models, it doesn’t really matter what kind of metrics we use.

Campbell’s law of corruption of measurement indicators applies here: “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor” (Campbell, Donald. “Assessing the Impact of Planned Social Change. Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol 2 (1979), p. 85). Gaming the FICO score in mortgage underwriting is a good example. What credible evidence is there that another type of metric would have fared any better?

-Neil Raden

Partner, Smart (enough) Systems LLC

Greetings Neil,

I think all your points are good but you are missing that the meaning of a score is unclear. The meaning of a probability is not. For example, “an indication of credit worthiness” is less clearly useful than “a probability of default”. Of course, the accuracy of the output is also important. The lack of clarity of what a FICO score meant to its market was a factor (according to the speaker). I’m comfortable with Campbell’s perspective on quantitative metrics that have no fundamental semantics, but if it’s a probability it is inherently resistant to pressure, distortion or corruption. This point was driven home by Mr. Ayers. BTW, I don’t blame FI for marketing something other than a probability. It’s easier, practical and liability limiting.

I’m very late to this conversation but couldn’t resist adding my own two cents here. Paul I see and respect the point you are making but I guess I just see this issue from a different perspective. I absolutely agree that the FICO score is less mathematically clear than a probability but given it’s purpose in life that’s not a bad thing. It’s intended to be more of a general indicator that has to appeal to a very wide audience. The audience not only being multiple types of lenders/creditors but also consumers. In addition to being a measure of general credit worthiness to business, it also has to be understandable and actionable by consumers. This is to the extent that it can be explained why their score is what it is and what actions can be taken to change it. I think a score model does a much better job of presenting this to the wider audience than a probability. Probabilities are more accurate but they are also harder to explain.

Unfortunately, the FICO score has been interpreted to be much more than this by lenders which may have contributed to the current mortgage mess but how much is debatable. While the FICO score may have been misinterpreted I don’t believe that it has been misrepresented by Fair Isaac. Clearly the FICO score by itself is not enough to base a lending decision on especially given the number of new and creative loan types (some down right predatory but that’s a different discussion) that have appeared over the last decade. Times have changed and lending decisions haven’t kept up. New and more sophisticated measures are needed to evaluate things like loan product suitability and probability of default. These measures require more information that is specific to the borrower (e.g. Job History, Expected Hold Time, Job Compensation Structure, etc.), region, industry (mortgage, auto, etc.) and many other factors. I think the FICO score still has a place here but as an input to the more sophisticated measures instead of the end-all-be-all. I think the first pass at these new measures will require the collection of new customer data that’s either currently not used or not collected.

Of course none of this will matter if a business chooses to ignore or re-interpret these measures in the interest of short-term gain, which in my opinion has more to do with this mess than anything else. I saw examples of this on almost every mortgage project I worked on. In the case of sub-prime you could say that the FICO score was sometimes just plain ignored altogether. Risky loans were made available to those with either bad credit or no credit (stated, no doc). The originators didn’t have to carry the loan and the institutions that bought the loans in many cases just attempted to dilute them in larger securities. The incentive structures for brokers also enabled the pushing of the riskier loan products even when they were not the best fit for the borrower. Even the most sophisticated and accurate measures would not have helped if they were ignored because they were deemed to hurt short-term profits.

Sincerely,

Jeff Steelhammer