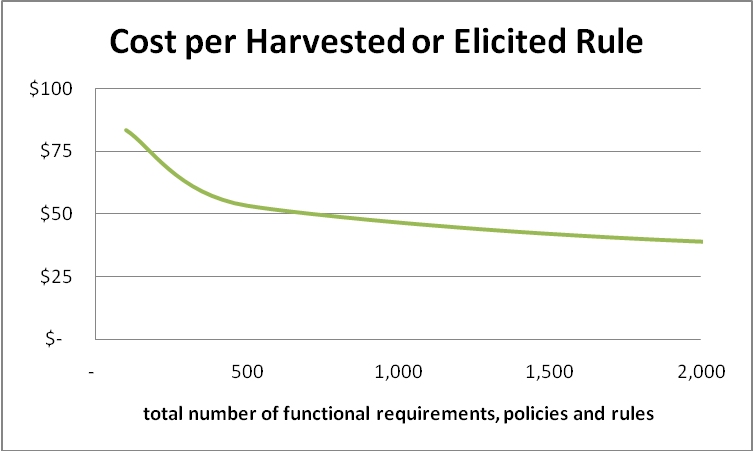

We have been teaching a computer to answer questions like, “How much did IBM’s earnings change last quarter?” It takes a fair bit of knowledge, including how to understand English, to answer this question. But teaching it what a “quarter” is brought back memories of debates with some former CMU colleagues about what units are and how to model time. Since quite a few people ask me for help with knowledge engineering and ontological matters, I thought some might be interested in parts of those debates.As you will see, a strong upper ontology of common knowledge is required to understand common business knowledge. Leveraging such an ontology is the only way to deliver business rules for under $50.

Sentences like “do something if more than a number of possibly related things have happened within a timeframe of something else happening” or “do something if nothing happens within a timeframe following something happening” are extremely common in business process management (BPM), complex event processing (CEP), and workflow. With a sense of time, a business rules management system (BRMS) can support BPM, CEP, and workflow applications almost trivially. Without a sense of time, most BRMS force users to perform computations.

For example, without a sense of time and an infrastructure that supports it, the sentence “call a customer if no response is received within 30 days of notifying the customer of a delinquency” has to be transformed into something like “if a notice is mailed on a date and the notice is a delinquency and the date of notification has a day number then compute the date for checking by adding 30 to the day number and check for a response to the delinquency notice on the date for checking”. The checking on a date for a response to a notice must also be implemented as a database (or persistent queue) of events to be polled or triggered by application code. Then a second rule is required to implement the check, as in “if checking whether a response has been received to a notice and the notice was given on a date of notice and the notice was given to a customer and there exists no record of communication with the customer since the date of notice then call the customer”. (Note that this is actually how most BRMS products would implement this. The natural language approach I prefer handles the original sentence.)

The discussion here reflects the general structure and content that a usable ontology for business process management requires. Most users of business rules management tools will find the need to understand and engineer this discussion in their tool of choice. As my Haley Systems customers know, much of this is reflected in Authority’s built-in ontology and English vocabulary, but quite a few of the points discussed here reflect improvements, especially concerning the confusion between units and amounts.

As you will see the discussion takes careful thinking. Some readers may find it onerous. If at any time you have had enough (or if you simply cannot take anymore!), please skip to the end and decide whether to fill in the conclusions by revisiting the body.

Continue reading “Understanding events and processes takes time”