The folks from Knowledge Partners have a post that I found thanks to Sandy Kemsley, whose blog often provides good pointers. This article talks about the decision perspective on business rules. It makes some good points, on which I would like to elaborate albeit at a more semantic or knowledge-level.

Every language has three kinds of statements: questions, statements, and commands. There are also some peripheral types, such as exclamations (Yikes!), but in business processes and decisions only declarative and imperative sentences matter.

From a process- or decision-oriented perspective, decisions are always phrased as imperative sentences. Otherwise, the statements reflected in any business process, whether you are using BPMN or a BRMS, are declarative sentences.

Decisions are imperative sentences because they state an action to be taken. For example, decline a loan or offer a discount. It’s really pretty simple. A decision is an action. Rules that don’t take actions are statements of truth. Such declarative statements of truth are perfect for formal logic, logic programming, and semantic technologies. It’s the action that requires the production rule technology that dominates the market for and applications of rules.

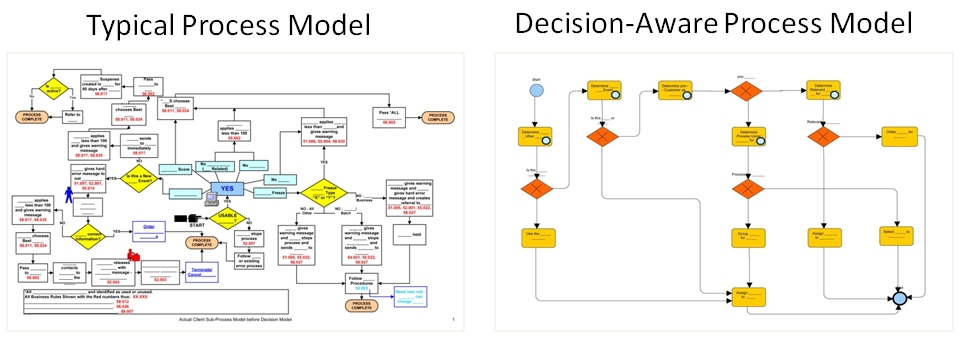

The authors of the aforementioned article use the following diagram to explain the benefits of the decision-oriented approach in simplifying business processes:

The impact is very simple. If you eliminate how you reach decisions from the flow that you diagram in BPMN things get simpler. It’s really as simple as realizing that you have removed all the “if” parts (i.e., the antecedents) of the rule logic from the flow chart.

So who in their right mind would use a business process tool to express any business logic?

For the astute reader, this glosses over the need for decisions to have fairly global access to the data underlying (i.e., required in order to make) decisions. The separation of models and data between BPMS and BRMS should be avoided to address this. SOA helps, but there are important details (e.g., stateless?) [We’ve also written elsewhere here (how’s that for an oxymoron?) about the need for decisions to understand context, both with regard to the state of the business process or events that trigger processes.]

But wait, there’s more! Where did the business process we’re looking at on the right come from? Where is it documented (or enforced!) that a loan should not be approved without first checking credit? Is there any path to approving a loan for which checking credit is not a prerequisite? Who drew this graph? How do we know it’s right? [I’ve written elsewhere about the need for governance of business processes, of which this is the simplest form of example.]

Are you getting the picture? Business process diagramming is still programming, visual as it may be. This pigeon-holing of rules technology is wrong. Raising the understanding of decisions as central is important, even critical. But thinking that knowledge must be expressed as rules that coallesce complexity into boxes tied with bows within in pretty diagrams is naive. The right perspective is that both the flow chart and the logic are driven by the knowledge captured about the organization and its operational and governing policies.

Most people would agree that if-then rules are technical tools. Many would agree that BPM tools are best left in the hands of IT. More are realizing that each should be driven more by knowledge about business and constrained less by the shallower by still steep waterfall relationship between the executive suite and technologists.

Decision management is important but it is only a piece of the pie. Knowledge management – not the 90s notion of content management but knowledge that is curated and understood rigorously enough to generate and govern process and decision diagrams and logic, respectively – is where the strategic CIO needs to aim.