What is the part of speech of “subject” in the sentence:

- Are vitamins subject to sales tax in California?

Related questions might include:

- Does California subject vitamins to sales tax?

- Does California sales tax apply to vitamins?

- Does California tax vitamins?

Vitamins is the direct object of the verb in each of these sentences, so, perhaps you would think “subject” is a verb in the subject sentence…

A colleague who is expert in such matters points out that if “subject” was a verb, then it would be more correctly stated in the passive using “subjected”. (It is certainly not the case that vitamins subject.)

In the English Resource Grammar (ERG), it turns out to be an adjective, which may seem counter-intuitive (as it did to me at first glance).

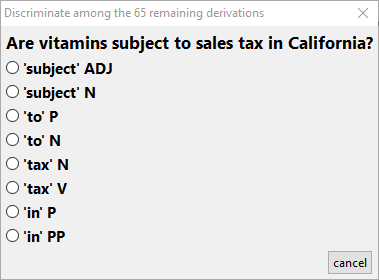

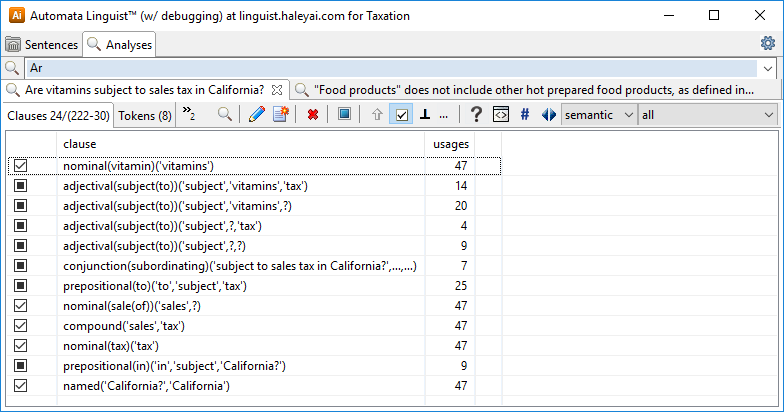

It became more apparent when the Linguist prompted as follows after parsing the sentence without parts of speech (if so configured):

Note that there is no verbal part of speech in any of the 65 different lexical, syntactic, and semantic parses returned for this simple sentence.

There is much about natural language that is confusing to machines, as demonstrated by the large number of parses for even such a simple sentence[1].

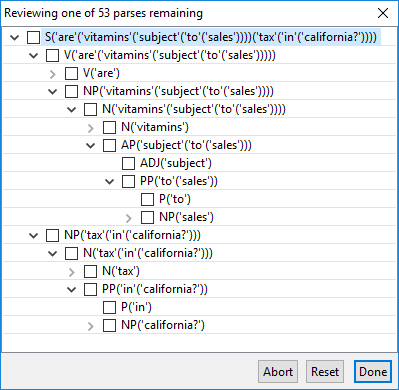

Consider the parse that a maximum entry model selected as “best”:

Consider the original sentence with “subject to sales” as an adjectival phrase and “tax in california” as a noun phrase. The latter is clearly plausible and the machine is perfectly satisfied with something being subject to sales (as it would be with subject to tax).

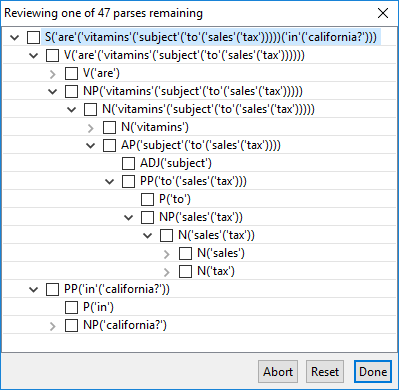

Once we clarify that “to tax” is not actually a prepositional phrase in this sentence, the highest ranking parse that survives looks like:

From the machine’s standpoint, this is perfectly reasonable, but the meaning (i.e., the semantics) of this parse is wrong. We are not asking if some vitamins are in California, after all!

There are many ways to disambiguate this sentence using the Linguist, but for the sake of concluding this article, let’s advise it that the noun phrase shown above is incorrect (since it does not include “in California”).

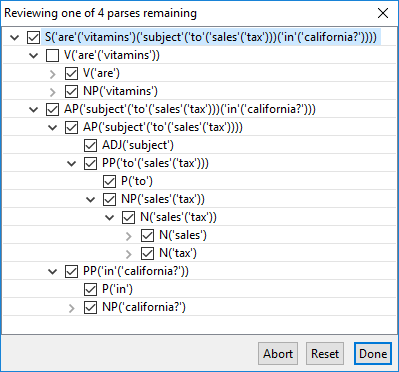

We confirm this parse and have only 4 remaining. Without going too far into the remaining subtleties, consider the following semantic “discriminants”:

Essentially, these parses are considering the ambiguity of “to” as part of the adjectival construction versus the possibility that it introduces a prepositional phrase, but such linguistic details are of little concern (i.e., we don’t have to be a linguist to see what choices make sense).

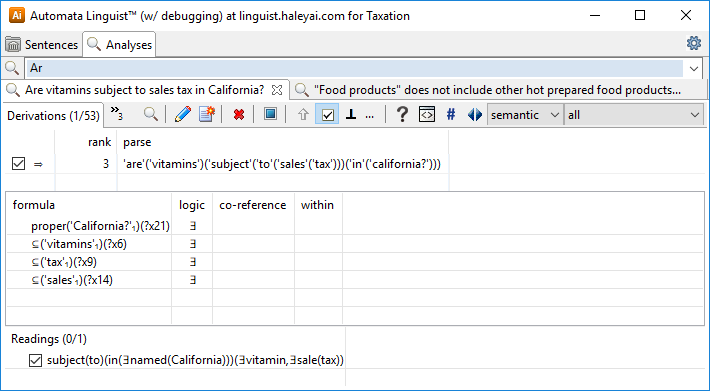

After selecting the first adjectival above all ambiguity is resolved, as shown below in the fully “conflated” rendering of the logic of the question below.

Details on this conflation are in the second patent listed at LinkedIn. For our purposes, this representation is sufficient for a logic programming system to answer the question.

[1] For the interested reader, unless the input tokens are tagged with parts of speech, the ERG considers all possible interpretations of the text given its extensive grammar and lexicon. A proper partial tagging of this sentence might be “Are vitamins subject/ADJ to/P tax/N in/P California?”, which resolves all the ambiguities displayed in the dialog shown above, in which case, the Linguist returns 22 parses.